This blog explores post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the context of developing early childhood interventions in low/middle income countries (LMIC’s). Children from LMIC’s have a higher probability rate of experiencing traumatic experiences, yet the vast majority do not have access to efficacious psychological treatments [1]. Improving access to mental health services is one of the grand challenges faced in global mental health research [2]. After outlining the background relevant research into the lifelong effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACE’s), this blog focuses on the benefits and challenges faced within school-based interventions for early childhood PTSD, before finishing with an example of a study of a school based intervention for PTSD in a LMIC that utilises paraprofessionals as facilitators.

Life Course Consequences

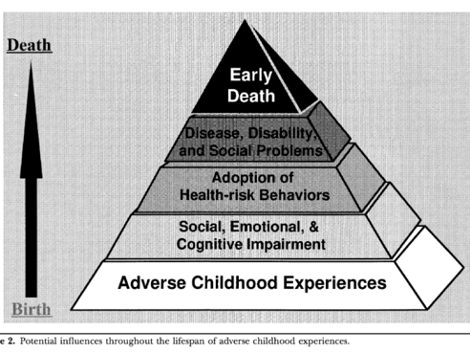

Felitti et al.’s 1998 study [3] into adverse childhood experiences retrospectively asked adult participants to identify adversity they experienced during childhood, and explored for correlation with physical health over the life span. There findings demonstrated how adversity experienced during childhood can translate into life-long health, social and cognitive implications, which can ultimately lead to an early death. Although this theoretical framing of trauma emerged from a population of adults from high income countries (HIC’s), studies have demonstrated that the ACE questionnaire also identified that the model applies to LMIC, some of which have particularly high rates of childhood adversity [4].

In extrapolating childhood adversity as an underlying causal factor in later adult health issues, the ACE study also alludes to the positive consequences of interventions that successfully address and resolve the adverse experiences therapeutically. Namely, that the consequences may span beyond immediate improvements to a participant’s mental health, altering their life course trajectory. This life course perspective is also adopted in the justification for increased investment into early childhood interventions [5] [6].

Applying this rationale onto working with children to address PTSD may also represent a valuable return on investment. To give a reductionist example to illustrate the point, it might be cost less to resolve the underlying adverse experiences through therapeutic interventions whilst the individual is still a child, otherwise if they later develop alcoholism, the subsequent remedial medical efforts because of their liver failure may be far more costly compared to the early childhood intervention.

The lack of LMIC research

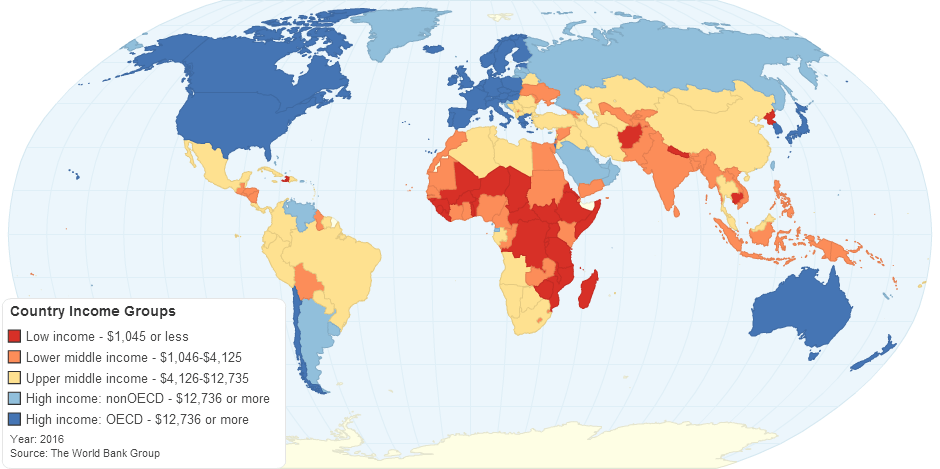

In a meta analysis of 24 studies, Newman et al. found that psychological interventions, predominantly cognitive behaviour therapy based protocols, are an effective post-disaster treatments for children with PTSD [7]. However, there is a large paucity in research into child and adolescent mental health interventions in LMIC’s compared to HIC’s [8]. Indeed, between 2001 and 2010, 90% of randomised control trials into child and adolescent mental health disorders were on HIC populations [8][1].

[16]

Regarding PTSD, of 1000 reviewed articles containing adult and child populations, only 12.7% contained sample populations outside of HIC’s [9]. making LMIC’s significantly under represented. Furthermore, 57% of the articles were only available through journal subscriptions, demonstrating a barrier to access where LMIC researchers often rely upon open access publications [9].

Why School based?

School based mental health programmes are a key strategy in addressing the paucity of mental health interventions for children in LMIC [1]. In a meta analysis of 19 studies, 8 of which were either LMIC’s or refugee populations, Rolfsnes and Idsoe found that school based interventions have a medium to large effect on reducing symptoms of child PTSD [10] Furthermore, interventions delivered in school settings led to considerably more students accessing and completing free treatment for PTSD after Hurricane Kutrina, compared to treatment in a clinical setting [12]. This highlights how convenience of location and familiarity of setting are factors can affect treatment outcomes, and that placing interventions within the school setting can overcome particular barriers to access.

Challenged with school-based interventions for PTSD in LMIC

Utilising teachers that are already overburdened with their daily tasks and responsibilities is challenge faced with integrating mental health interventions in a school setting [1]. Despite this, studies have found that utilising existing professionals to deliver mental health interventions at schools can be successful [10]. Inadequately trained health care professionals and teachers, as well as parents, with a lack of mental health knowledge is a barrier in identifying and diagnosing children with mental health issues [1]. This is a particularly nuanced challenge, considering how PTSD shares multiple clusters of behaviours and symptoms with other diagnostic classifications, such as depression and anxiety based disorders [11].Furthermore, the fact that individuals will react differently to adversity even when they are shared traumatic experiences, and that not everyone will develop symptoms of PTSD [10], represents further challenges in selection criteria for access to interventions. Indeed, Dybdahl found that children’s symptoms of distress following similar exposures to combat violence widely differed [13].

An Example of school-based child PTSD intervention in LMIC

[15]

In a study of 495 children, with a mean age of 9.9, Tol et al. designed a program of 15 group trauma therapy sessions, for children affected by political violence in Indonesia [14]. The program was manualised, based upon efficacious trauma processing creative activities, and was delivered by trained paraprofessionals after 5 weeks of training.

This simultaneously overcomes the challenge of over-burdened teachers, and the lack of mental health professionals in LMIC’s. Although the study only achieved modest results in decreasing PTSD symptoms of treatment group compared with the waiting list group, and had several methodological limitations, [14] it is included here because it represents a novel intervention design that attempts to overcome barriers to access of mental health interventions, by creating lower cost methods of implementation through the utilisation of paraprofessionals.

Conclusion

This blog has explored the nature of the life course effects of children’s experiences of adversity, whilst highlighting the current paucity in child mental health research in low and middle income countries. School based interventions are a key strategy in improving attendance and outcome in interventions, and utilising paraprofessionals may help to overcome some of the current barriers to scaling the implementation of child PTSD interventions.

Thanks for reading!

References

[1]. Patel, V., Kieling, C., Maulik, P. K., & Divan, G. (2013). Improving access to care for children with mental disorders: a global perspective. Archives of disease in childhood, 98(5), 323-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302079

[2] Collins, P. Y., Patel, V., Joestl, S. S., March, D., Insel, T. R., Daar, A. S., … & Glass, R. I. (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature, 475(7354), 27-30. https://www.nature.com/articles/475027a

[3] Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

[4]. Manyema, M., & Richter, L. M. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences: prevalence and associated factors among South African young adults. Heliyon, 5(12), e03003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03003

[5] Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., … & Devercelli, A. E. (2017). Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. The Lancet, 389(10064), 77-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

[6]. Doyle, O., Harmon, C. P., Heckman, J. J., & Tremblay, R. E. (2009). Investing in early human development: timing and economic efficiency. Economics & Human Biology, 7(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2009.01.002

[7] Newman, E., Pfefferbaum, B., Kirlic, N., Tett, R., Nelson, S., & Liles, B. (2014). Meta-analytic review of psychological interventions for children survivors of natural and man-made disasters. Current psychiatry reports, 16(9), 462. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-014-0462-z

[8]. Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., … & Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515-1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

[9] Fodor, K. E., Unterhitzenberger, J., Chou, C. Y., Kartal, D., Leistner, S., Milosavljevic, M., … & Alisic, E. (2014). Is traumatic stress research global? A bibliometric analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 23269. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.23269

[10] Rolfsnes, E. S., & Idsoe, T. (2011). School‐based intervention programs for PTSD symptoms: A review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(2), 155-165.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20622

[11]Amaya-Jackson, L., Socolar, R. R., Hunter, W., Runyan, D. K., & Colindres, R. (2000). Directly questioning children and adolescents about maltreatment: A review of survey measures used. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(7), 725-759. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626000015007005

[12] Jaycox, L. H., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer, K. L., … & Schonlau, M. (2010). Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma‐focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 23(2), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20518

[13] Dybdahl, R. (2001). Children and mothers in war: an outcome study of a psychosocial intervention program. Child development, 72(4), 1214-1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00343

[14] Tol, W. A., Komproe, I. H., Susanty, D., Jordans, M. J., Macy, R. D., & De Jong, J. T. (2008). School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in Indonesia: a cluster randomized trial. Jama, 300(6), 655-662. doi:10.1001/jama.300.6.655

[15] Suhartono, M., Victor, D. 2019. Violence Erupts in Indonesia’s Capital in Wake of Presidential Election Results. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/world/asia/indonesia-election-riots.html

[16] World Bank. 2016. Country Income Groups (World Bank Classification). Retrieved from: http://chartsbin.com/view/2438

I like the way you presented your blog, Ben. This is a great topic. You highlighted carefully the key points as well.

This is sad that mental disorders in general are underestimated and unexplored in LMIC. Logically, those mental disorders are expected to have higher prevalence rate in low-resource settings, because life is harder, and there is less mental support available; but there are more stigma and discrimination related to mental disorders (Saraceno et al., 2007). Although, this seems obvious that like any early intervention, interventions that address mental illnesses at an early stage guarantee the lifetime benefits for the children and they are cost-effective.

Indeed, school appears to be the safer place for children facing mental issues, particularly in humanitarian contexts such as war-affected children or refugees who are most of the time suffering from PTSD (Tol W.A., 2014). School acts as a means for mentally ill children to adjust to a new environment, as well as allows them to benefit freely from the program (Rousseau C., 2008).

In terms of research, evidences have shown that, compared to other non-contagious diseases, little concern has been given to mental disorders in LMIC (Hofman et al., 2006). In fact, this is one of the reasons why well-qualified researchers from LMIC flee to HIC searching for better work conditions. Thus, in order to include programs that focused on mental health within the health systems in LMIC, the WHO identified various barriers, such as the lack of well-trained human resources and the cultural acknowledgement of these programs by the local population (Patel et al., 2011).

The reality in low resource settings puts physical health demands prior to mental health well-being, because these sustain life (Jacob, 2001), this is better illustrated in the” Maslow’s Hierarchy of individual needs” (Costa P.T., 2000).

Well done!

LikeLike

Sorry, here are my references:

References

Costa P.T., &. M. (2000). Approaches derived from philisophy and psychology. In K. &. Sadock, Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (p. p.642). Philadelphia: 7th edn (eds B.J. Sadock & V.A. Sadock).

Hofman K, R. A. (2006). Reporting of non-communicable disease research in low-and-middle-income countries: a pilot bibliometric analysis. Journal of Medical Library Association, 94(4):415–20.

K.S., J. (2001). Community care for people with mental disorders in developing countries. Problems and possible solutions. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178; 296-298.

Patela V., C. N. (2011). Improving access to psychological treatments: Lessons from developing countries. Behav Res Ther., 49(9): 523–528.

Rousseau C., G. J. (2008). School-Based Prevention Programs for Refugee Children. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am, 17: 533–549.

Saraceno B., V. O. (2007). Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet, 370:1164–1174.

Tol W.A., K. I. (2014). School-based mental health intervention for children in war-affected Burundi: a cluster randomized trial. BioMedCentral Medicine, 12:56.

Tatamo.

LikeLike

Addressing childhood post trauma stress disorder or simply PTSD in low middle income countries is very interesting topic. I am totally agreed with you that children from LMIC’s have faced enormous troubles and problems both physical and mentally as well. This developed stress, anxiety and depression from their early childhood. Also, they have no access to efficacious psychological treatments. You blog have explored several good points in term of life course consequences and identify adversity they experienced during childhood as well as explored the impact on physical and mental problems. You have also very clearly provided comparison of the impact between low income and him income countries; however, I would like to add one point here that if you specially identify the countries like the UK, US and other as high income countries and Yemen, Afghanistan or others as low income countries may demonstrate better understanding. You have provided good theoretical perspective of the topic and explained well through lifespan of adverse childhood experience triangle. Further, you have provided meta-analysis to support different interventions and programmes. You have provided the most important intervention for PTSD in LMIC and their challenges. I agreed with this that and I found similar challenges in my blog as well that inadequate trained healthcare professionals, teachers and parents with lack of knowledge about mental health are key issues in identifying and proposing effective interventions for children with mental health issues.

LikeLiked by 1 person